Rhode Island is the second most densely populated state behind New Jersey, with the second highest coastline-to-land area ratio. Most of its population is located along the coast of Narragansett Bay. Union, unsurprisingly, has worked on projects in our home state faced with rising sea levels. Through our work we’ve seen and developed multiple strategies, each one being what fundamentally worked for the community and its economic drivers.

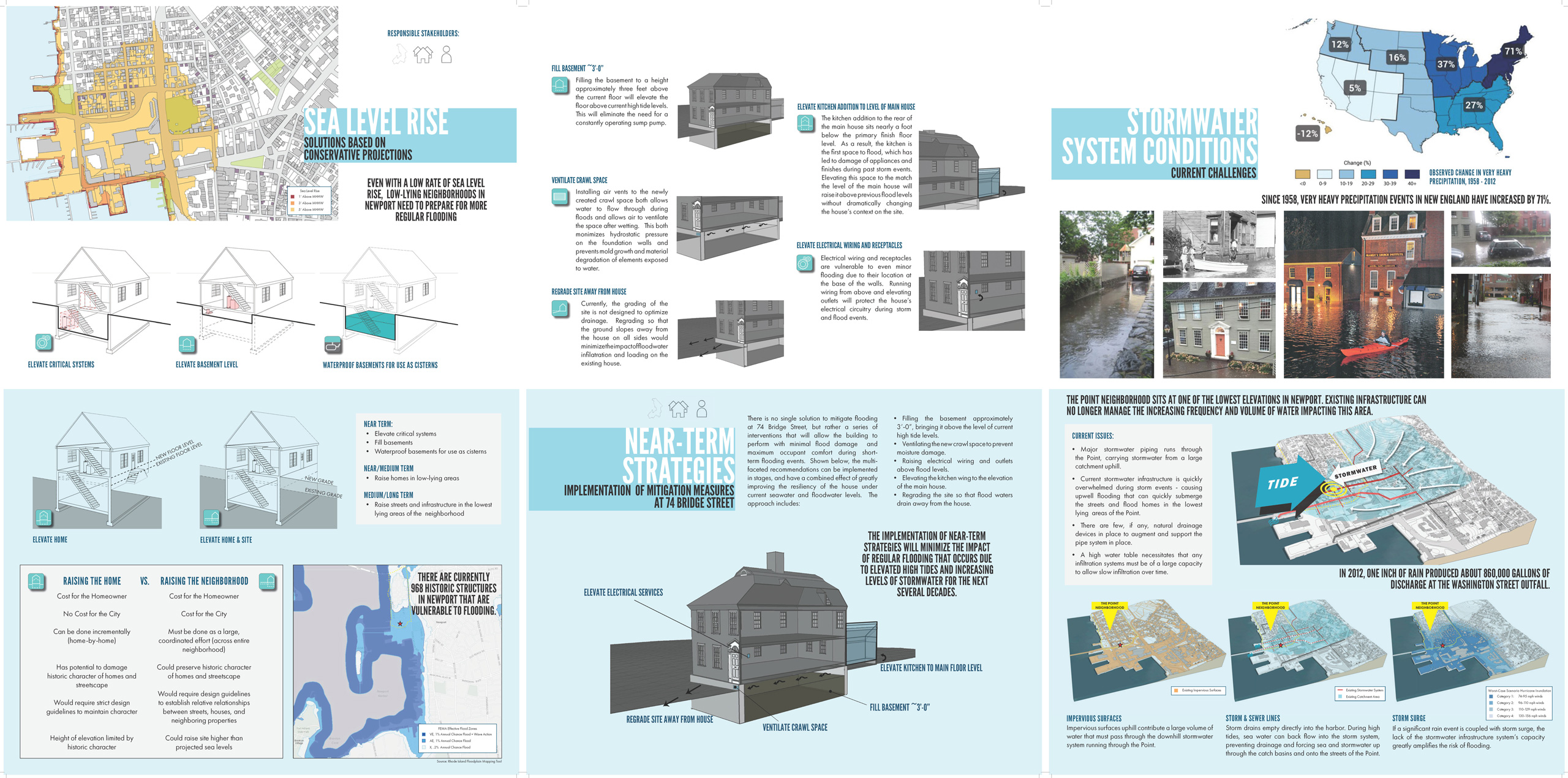

Newport’s waterfront has consistently remained an economic driver for the city, whether as a conduit for exporting goods in the 19th century, ongoing U.S. Naval ties, or tourist attractions as of late. Throughout its history, one thing has remained constant: Newport, “the City by the Sea,” is inexorably bound to the water–for better or worse. Newport’s rich past has been well-preserved through its architecture, helping to fuel the tourism economy; but Newport’s thriving waterfront is increasingly under existential threat due to flooding from ever more frequent storm events and rising tides.

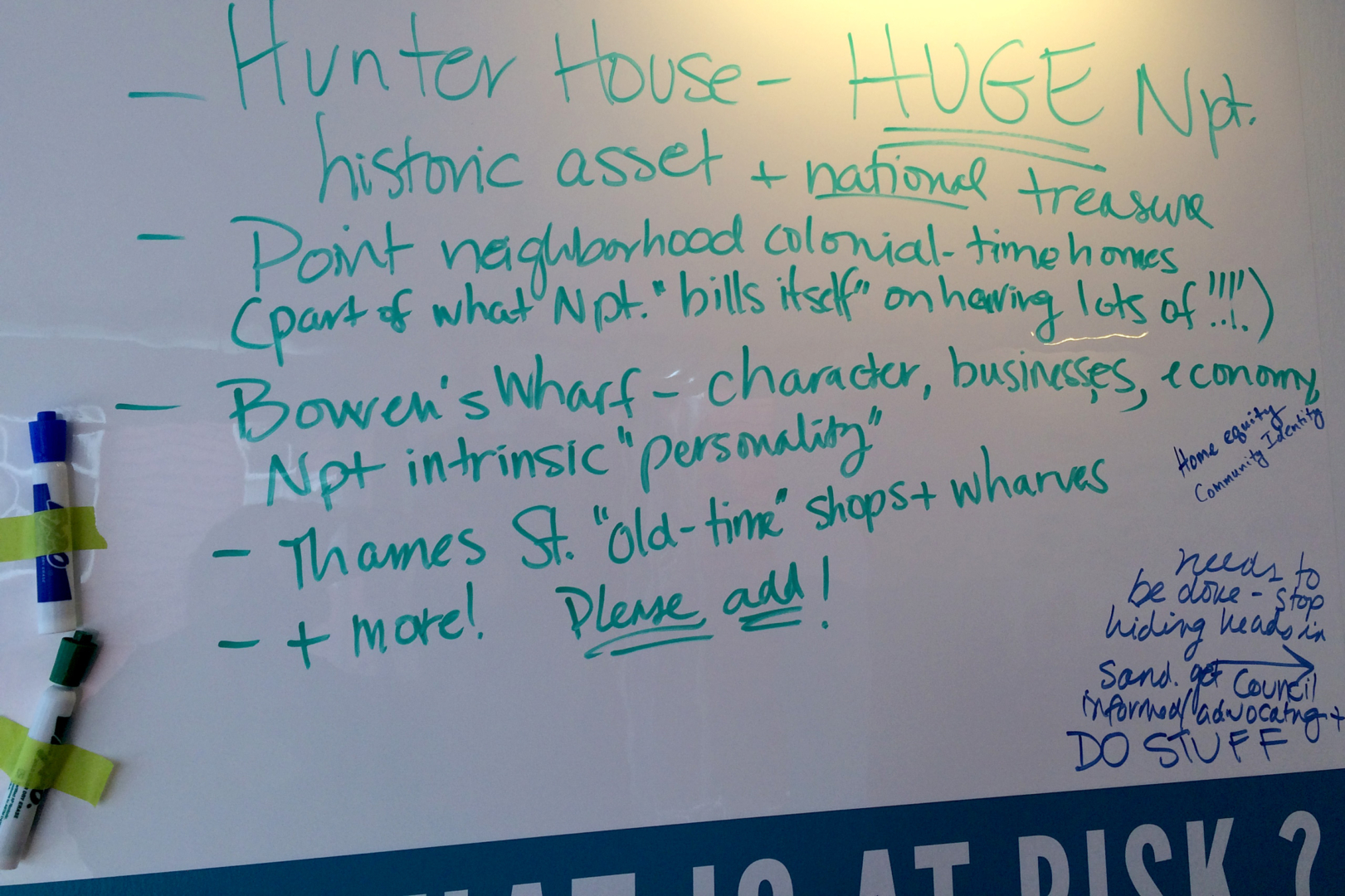

In the fall of 2015, the Newport Restoration Foundation engaged a collaborative team of architects, engineers, and preservationists to undertake a case study of a recently acquired historic home in Newport’s Point neighborhood with the explicit goal of exploring the impacts of sea level rise on our historic waterfront resources. Union led the team in an exploratory two-day charrette attended by engineers, planners, landscape architects, and neighborhood residents. The outcome of the charrette focused largely on climate change impacts from rising sea levels and stormwater inundation from severe precipitation events–challenges that are affecting every part of the Ocean State, not just Newport.