by Joel VanderWeele

Union is in the process of designing one of the first multifamily buildings in Rhode Island built to the Passive House standard. What does that mean? And how do we combine this new-fangled high-tech energy efficiency standard with our commitment to traditional town planning and architecture?

Let’s start with the basics – what is Passive House?

Passive House is a performance-based energy efficiency standard which aims to reduce annual heating demand by 80-90% and overall energy use by 60-70%. It was developed and defined as the cost optimal, competitive sweet spot between conservation and generation on the path to zero energy. The standard is administered by a non-profit called Phius in the U.S. and by the Passive House Institute in Europe.

The Passive House movement has been around since the 1970s, but has gone in and out of fashion – at least in the U.S. – as oil got expensive (1970s – 1985), then cheap (1985-2000), then expensive again (2000-present). The current iteration has been gaining traction, and with the reality of climate change finally reaching mainstream acceptance, it is here to stay.

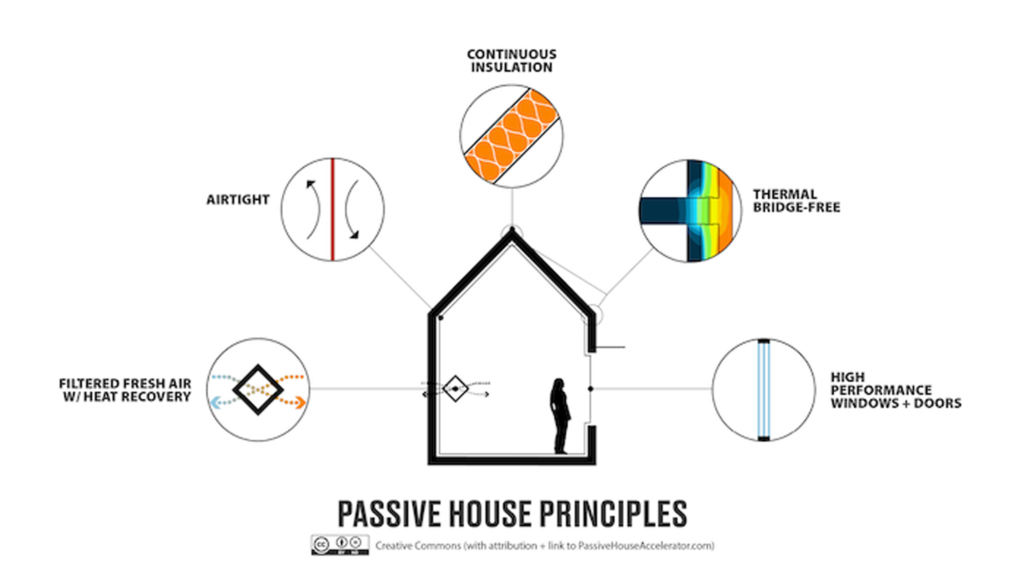

The official design principles of Passive House are:

- Continuous insulation, no thermal bridges

- Air-tight construction

- Optimized window performance and solar gain

- Balanced heat/moisture recovery ventilation

- Minimized mechanical system

The insulation, airtight construction, and windows work together to keep the temperature inside stable – not taking huge swings throughout the day/week/year. The ventilation system ensures that the fresh air you do bring in is tempered before it comes inside – like if you cracked a window but only air that was between 60 and 80 degrees was allowed inside. And all this investment in your thermal envelope and ventilation means that you can keep your heating and cooling system very small. Altogether, the focus of these design principles is on reducing operational energy demand in your building, so you can keep residents comfortable with as little energy input as possible.

A common critique of Passive House relates to the air-tightness requirement. People often say that “buildings need to breathe” but that’s not really true; humans need to breathe – buildings need to dry out. While it is true that drafty old buildings that “breathe” dry out quite well, they do so by allowing the conditioned air out in the winter and unconditioned air in during the summer. That puts a greater strain on the mechanical equipment, burning more fossil fuels, increasing utility bills, and decreasing occupant comfort. If you design to the Passive House standard, you get a building that can dry out without paying a penalty on your conditioned air.

The Passive House movement is an important one, and with three Certified Passive House Consultants (CPHC) on staff, Union is doing what we can to stay up to speed on the latest building science and promote this standard to our clients. But it’s only part of the equation; it is a necessary but insufficient lens through which to evaluate a building.

Before layering on the rigorous Passive House standard, before working through air sealing details, before specifying high-efficiency heat pumps and ventilation equipment, Union’s first step is to apply the design principles that have been established over time that have resulted in buildings (and communities) that are useful, durable, and beautiful.

This commitment to tradition is not about nostalgia – although there is something to be said for creating buildings that give people a sense of comfort and familiarity. The architectural forms and details that have been developed over time are the hard-won result of trial and error. They get re-used and refined and eventually become part of the regional vernacular because they work well in that particular climate, culture, and economy. Pitched roofs with overhanging eaves, compact building form with optimized solar orientation, window size, trim profiles… all of these elements contribute to the long-term performance of a building. Passive House does not un-do these lessons learned throughout history; in fact, those details almost always improve your Phius-required energy model.

Breakthroughs in building science can be used to further the inherited wisdom of tradition. Image from Marc-Antoine Laugier’s Essai sur l’Architecture.

So where does Passive House fit into the “useful, durable, beautiful” rubric mentioned above? Passive Houses are more comfortable to occupy, so in that way, they are more useful to their residents. And the durability of a building also depends on how easy it is to maintain – so by keeping utility costs down, Passive Houses are more durable and resilient.

Phius is agnostic about beauty, but we are not. A beautiful building is more likely to be loved, and a well-loved building is more likely to last, so it’s important to not get so caught up in optimizing energy performance that beauty is an afterthought. It is as integral to your building’s sustainability as air changes per hour.

One other thing to note is that Phius is focused on the object of the building – it is silent about context and community. This is not a critique, just the reality of an organization promoting energy efficiency in construction. But the purpose of a building is to support human life, and humans rely on other humans to flourish, so it is important for architects to create buildings that relate to each other in a way that supports and promotes community and preserves the natural landscape.

By bringing together the inherited wisdom of tradition and the latest breakthroughs in building science, Union produces truly sustainable buildings and communities.

In a similar sustainable vein, we’ve been thinking about:

- Embodied Carbon vs. Operational Efficiency – Is it worth it to use carbon-intensive products like spray foam and extruded polystyrene to achieve long-term operational efficiency?

- Futuristic Materials vs. Proven Durability – Many of the materials we use to create super-insulated, air-tight buildings – tapes, sealants, vapor variable air barriers – haven’t been around long enough to know how they will perform over the (hopefully very long) life of a building.

- Individual vs. Collective Sustainability – If you build a passive house in the middle of the forest, is it sustainable?